April 29/May 6, 2019: Volume 34, Issue 24

By Reginald Tucker

Some of the key economic policies instituted by the Trump Administration were designed to reduce the tax and regulatory burden on U. S. corporations to create an environment that would attract (or retain) investment in domestic manufacturing.

Some of the key economic policies instituted by the Trump Administration were designed to reduce the tax and regulatory burden on U. S. corporations to create an environment that would attract (or retain) investment in domestic manufacturing.

This change would improve the absolute ROI on U.S. investment, motivating and enabling all U.S. companies to grow faster by investing at home. At the same time, the U.S. ROI would be improved vs. offshore investments, leveling the playing field with some of our primary trading partners—namely China—by encouraging U.S. manufacturers to take advantage of lower taxes by reinvesting in their stateside operations. The changes would also encourage those companies who already produce outside the U.S. (or are planning to do so) to “reshore” those operations and bolster their domestic capacity and, by extension, American jobs.

FCNews recently caught up with Harry Moser, founder and president of the Reshoring Initiative, and an authority on all things concerning domestic manufacturing, to discuss these issues. More importantly, to find out if the stated objectives are meeting the intended goals.

Following are excerpts of that conversation:

Is there a direct correlation to the number of manufacturing jobs coming back to the U.S. and the Trump Administration’s policies on taxation, trade and tariffs?

There’s a direct correlation between these government actions and the reshoring trends. The lower tax rate—specifically taking it down from 35% to 21%—makes the return on investment in a U.S. facility much more competitive than it was before. Also, the immediate expensing of capital equipment helps companies finance the investments. In the past, suppliers had to depreciate any new equipment they purchased over the course of seven years, basically for tax purposes. Now, they can write off the equipment in the same year in which they made the investment. This includes a factory, machine tools, a steel mill—whatever. This helps reduce their tax in the current year because they have all that depreciation. However, it hurts suppliers in the second year/third year because they don’t have those years of depreciation. It shifts those write-offs forward to the year in which those expenditures are made. This definitely motivates business owners to invest in capital now.

Research shows the U.S. economy saw a bump in 2017 as a result of the tax cuts. Has that spilled over into 2018?

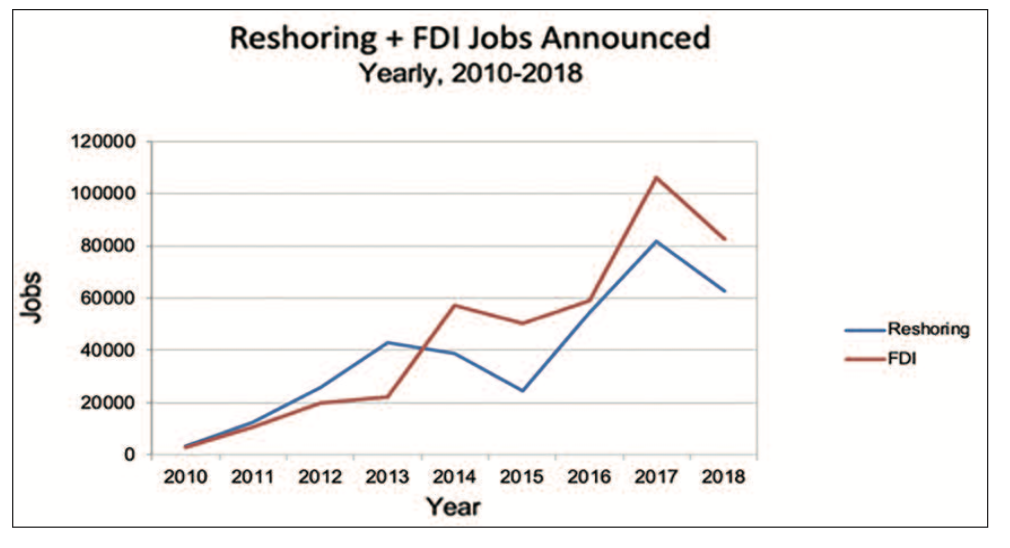

In 2017 we had 170,000 (announced) manufacturing jobs come back to the U.S. But in 2018 the responding number was 145,000—down 14.7% from the year before. However, it’s still the second highest number of manufacturing jobs reshored, and it’s two or three times the average of the last 10 years, excluding 2017.

To what do you attribute the lower number in 2018 compared to 2017?

We believe it’s because of the uncertainty caused by the trade war with China and all the issues with the tariffs. It’s a lot of back and forth. Companies don’t know what’s going to happen with the supply chain or the market. Therefore, the easiest thing for them to do is stay in a holding pattern. But it’s all relative; if we didn’t have such a huge year in 2017, we would be bragging about 2018, because it’s up a lot from 2016.

Looking at the various manufacturing sectors, what industry was most impacted in 2018?

Most of the falloff in the reshoring numbers—specifically two-thirds—was in the auto- motive category. So if you look at the number of companies announcing reshoring jobs and/or foreign direct investment (FDI)—they’re up 35% from 2017 to 2018. But we didn’t have as many of the big gains when, for example, Nissan or Toyota puts in a whole new assembly plant. Announcements such as these typically result in the reshoring of 3,000-5,000 positions, not including the smaller, local suppliers who add anywhere between 500 and 1,000 jobs to support the additional capacity. Most industries were OK, but the transportation equipment number was off substantially.

Do you expect to see companies continuing to reinvest?

We saw a decent rise in capital expenditures, but now it’s tailing off a little bit. Again, that’s due to all the uncertainty surrounding the China tariffs—the aluminum and steel tariffs and the threat of automotive tariffs.

Is this strategy sustainable?

President Trump keeps bringing up new stuff—I think he has too many balls in the air. If he had just stuck to, ‘Hey, we’re going to fix the trade deficit’ and maybe left all our trading parts alone and just focused on China—and perhaps gotten all of the other countries to help him—I think he’d be in a much better position today than having put aluminum and steel tariffs on our allies and threatening them with various actions. I think the reshoring numbers and FDI numbers would be much better if he had done that.

Where do we stand today on trade with China?

The Chinese trade surplus with the U.S. is about $400 billion a year in their favor in terms of goods. By comparison, the Chinese trade surplus with the world is about the same number. So when you boil it down, China is “trade-neutral” (or trade balanced) in aggregate with the rest of the world, but it has a $400 billion a year trade surplus with the U.S. That represents about half of our total goods trade deficit.

The Chinese trade surplus with the U.S. is about $400 billion a year in their favor in terms of goods. By comparison, the Chinese trade surplus with the world is about the same number. So when you boil it down, China is “trade-neutral” (or trade balanced) in aggregate with the rest of the world, but it has a $400 billion a year trade surplus with the U.S. That represents about half of our total goods trade deficit.

When you look at the numbers, you might say, “Damn, it looks like China is intentionally beating up the U.S., shipping us its exports (toys, clothing, refrigerators, electronics, TVs, cell phones, etc.). Either they have focused on the U.S. or we’ve been totally negligent in not producing the things we should have been making but did not.

Why has there been this imbalance for so long?

Economics. Fifteen years ago, Chinese wages were about 3% of the U.S. level. Which means it costs substantially less to produce there. Also the Chinese government was very flexible to support investment by domestic and foreign firms. At the same time, the U.S. has set itself up as the dumping ground for imports by having a currency that is 20% overvalued and no value added tax.

We seem to be at a standstill in terms of a long-term resolution.

Trump is looking at that same data and has every right to bitch and say, ‘This isn’t fair and we have to fix this.’ I support his efforts in this regard, but I would have been much more focused on getting the allies on board; I would have negotiated with China in private before- hand and given them a chance to agree “voluntarily” instead of beating them up in public, because if they agree to anything now they’re losing face—and the Chinese don’t like to lose face.

Some of the companies that import from China began stockpiling inventories in advance of the tariffs with the fear a second round of tariffs would be forthcoming. This goes against the grain of the flooring industry model, which primarily functions on a “just-in-time inventory system.” What happens if there are no additional tariffs?

If it goes to 25%, you will have the inventory. But if it doesn’t you’ll want to get rid of it as fast as you can. Sounds like a good time for me to negotiate for flooring for my condo.

In the flooring industry, many companies that were primarily sourcing from China have partnered with manufacturers in other Asian countries in the wake of the tariffs. Are you seeing this across other sectors?

There has been a series of articles about work flooding out of China, with most of it going to Southeast Asia to places like Vietnam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, India.

Is it just a matter of time, then, before Vietnam becomes the new China and we’re dealing with the same issues?

That’s unlikely. Vietnam has about 96 million people compared to China’s population of 1.3 billion. Also, Chinese wages were rising 10-15% a year for the last 15-20 years. There are different dynamics in other parts of Southeast Asia. You don’t have to move too much work out of China to flood Vietnam with business. There are simply not enough workers in Vietnam to take the flood of work and not see the same wage growth patterns we’re seeing in China. So, five years from now, you might have to leave Vietnam. And by that time maybe Cambodia has gotten too expensive to produce. So now where do you go when that happens? India? (Has significant issues.) Africa? (I don’t see that.) Why go through a cycle like that every five years? Instead, we suggest U.S. companies do the math and find out the savings they will realize by coming back to the U.S.

But with high wages in the U.S., it’s not really cheaper to make products in the States.

It’s not that the U.S. is the best place in general to produce, but it is, in many cases, the best place to make products that are going to be sold here in the U.S. market. For example, U.S. companies are much more competitive selling flooring in the U.S. than they would be exporting to China, Germany, etc., because they don’t have to deal with duties, freight charges, inventory and so forth. U.S. manufacturing can be 15% more expensive than Chinese and still be the better choice for supplying the U.S. market.

Part of the challenge for companies that import is the high value of the U.S. dollar compared to other currencies. How do we address this issue?

We calculate that for every 1% improvement in U.S. suppliers’ costs vs. manufacturing off-shore, about 150,000 manufacturing jobs come back to the U.S. One of the simplest ways of achieving that is to bring down the value of the dollar. There’s a program called the Market Access Charge, which would charge anyone who wants to store money here—not to buy companies or hire people—a quarter percent to move the money into the U.S. That would motivate companies to move their money to Germany, Switzerland or maybe China, for example, which would lower the value of the dollar and raise the value of those other currencies. That, in turn, would make us more competitive. It would also make the U.S. a better place to build a factory—even if it doesn’t make us as good a place to be a bank. But the fact is, we need factories more than we need additional banks.

Interest rates play a role in that equation as well.

Lower interest rates are good for investment, and they’re also good for keeping the value of the dollar down. With a higher dollar value, U.S. bonds pay a higher amount and people think the dollar is going to keep going higher and higher. Then, billions of offshore dollars flood into the U.S. to get the higher interest rate and appreciation, and that keeps the cost of manufacturing in the U.S. uncompetitive vs. the rest of the world. One way to get the dollar down is to get the interest rates down again.