By Reginald Tucker

The negative impact of COVID-19 on human health was clearly swift and ferocious. But the pandemic’s impact on the global supply chain manifested itself slowly in the form of deficiencies in manufacturing, distribution and logistics.

All this has once again brought the subject of reshoring—the return of manufacturing jobs from overseas locations back to America—squarely into focus. The question today is, has the pandemic accelerated a reshoring movement that has, generally, gained steam in recent years? Or, has the move to bring back manufacturing to the U.S. naturally evolved on its own?

To help get at the answers, FCNews caught up with Harry Moser, one of the foremost authorities on all things related to onshoring and foreign direct investment in the U.S. As founder and president of the Reshoring Initiative—a nonprofit organization dedicated to bringing good, well-paying manufacturing jobs back to the United States—Moser helps companies more accurately assess their total cost of offshoring.

Following are excerpts of that conversation:

Bonafide trend or fluke?

Even before the onset of President Trump’s trade war with China—and long before he took office, in fact—researchers began to see significant movement in the return of manufacturing jobs from overseas back to the U.S. There has been some evidence that COVID-19, in conjunction with tariffs, has moved the needle further.

“Looking at the data going back to 2010, reshoring activity (plus foreign domestic investment in the U.S.) translated into roughly 6,000 manufacturing jobs returned to the U.S. that year,” Moser said. “By 2017, that number ballooned to 180,000. That number then declined in 2018 and 2019, primarily due to the trade war with China. The slowdown was likely due to business uncertainty as many companies decided to wait and see how it all played out until they thought about bringing more production back to the U.S.”

During the height of the trade war, opponents of the tariffs cried foul, arguing the tough measures were “against the rules of free market,” Moser said. “Now, everybody seems to agree that the U.S. has been shortsighted all these years in being so reliant on offshore production for all sorts of goods, including health-related gear—masks, gowns, gloves, drugs and antibiotics. Not to mention all the ingredients that go into the drugs that we already manufacture in the U.S.”

Danger of dependence

A case in point is the lack of PPE (protective personal equipment) for the nation’s frontline medical workers during the early response to the pandemic. Observers say this exposed America’s precarious reliance on items now deemed essential to effective healthcare delivery. It’s not that the U.S. doesn’t have the capacity to mass produce these items; it’s more of an issue of economics, labor rates and return on investment.

Moser put it in perspective: “Let’s say you’re only making 5% of the components required for masks. All of a sudden, like we’ve seen with COVID-19, the demand for masks goes up by a factor of 10. Now, in order to meet that demand, you have to increase your production by a factor of 200. So, why not buy it from other countries? Well, that’s not possible because they need them internally.”

Another alternative is to ramp up manufacturing stateside to meet the demand. However, it’s not that simple, Moser said. “In real-life manufacturing, you can’t do that in a week, or a month or six months,” he explained. “It’s one thing to double production—you might be able to run two shifts, add workers, etc.—but to go up by a factor of 200 is virtually impossible in a very short period of time. That’s especially true if we don’t make the components that go into specialized equipment such as ventilators, or the fabric that goes into the masks, or the machine that makes the masks, and so on. It’s a vicious cycle.”

Just as the trade war with China has created an overall “intellectual understanding” of the problems associated with offshoring, Moser noted, “COVID-19 has created a visceral and emotional response to offshoring by tapping into our basic survival instincts.” The situation has given many Americans a crude crash course in understanding the balance between open, fair trade and basic security.

To that end, Moser cited efforts by several U.S. senators and congressmen to eliminate America’s dependency on imported health care products, citing incentives put in place by the U.S. government. For instance, as part of the CARES Act, there’s a substantial amount of money—about $20 million—that has been put aside to help companies with a significant portion of that to help them reshore.

“Our dependency on imports of not just pharmaceuticals but also minerals, electronics, etc., has forced us to rely on offshore production from some unreliable sources,” Moser explained. “That has many asking, ‘How can we be the leading industrial economy when we’re dependent on so many things?’”

At the end of the day, Moser said, it’s not so much about outright nationalism as it is about mitigating supply chain risk. Given the fact we all participate in the “global economy,” observers say it’s difficult to extricate oneself from that economy and still prosper. But that’s not to say domestic production doesn’t have its benefits.

“In this age of COVID-19, people are recognizing the fact that you can’t get essential things when you need them,” Moser said. “In an ideal world, you would want your factory or assembly plant to have all its suppliers right next door. The idea is to minimize your risk by manufacturing locally, as opposed to having 100 risks scattered around the world.”

Drumbeat grows louder

Increasing interest among U.S. companies in bringing more manufacturing back onshore is reflected in the sheer number of inquiries the Reshoring Initiative has been receiving from new and existing clients alike these past two months. Moser reported he is fielding 10 times more prospects today than he did this time last year.

There’s more evidence of growing demand. Moser reported an increase in the number of manufacturing extension partnerships (MEPs) around the country. This network of companies, created by the U.S. Commerce Department, obtains funding from the federal government as well as the states in which they operate. Some MEPs are also funded via the services they provide to clients. “Their job is to strengthen U.S. manufacturing, especially small- to medium-sized enterprises,” Moser explained. “I would imagine most flooring manufacturers fall into this category.”

Seismic shifts

Prior to COVID, the U.S. saw a fair amount of U.S. companies that once imported flooring to the U.S. switch to sources outside of China (namely Vietnam and Cambodia), primarily as a means to circumvent the tariffs the Trump Administration placed on Chinese-made products. It’s unclear whether those companies are going to re-examine these newfound relationships yet again and focus more on bringing production stateside.

“If some of these companies were able move from China to Vietnam, they can certainly move production back to the U.S.,” Moser explained. “It’s really about understanding the total cost of ownership when making a decision as to whether you really save more money by producing offshore as opposed to manufacturing locally.”

Of course, establishing (or re-establishing) stateside production requires tremendous capital investment, including equipment, personnel, training and real estate. But in the long term, Moser said he believes it might be well worth the risk.

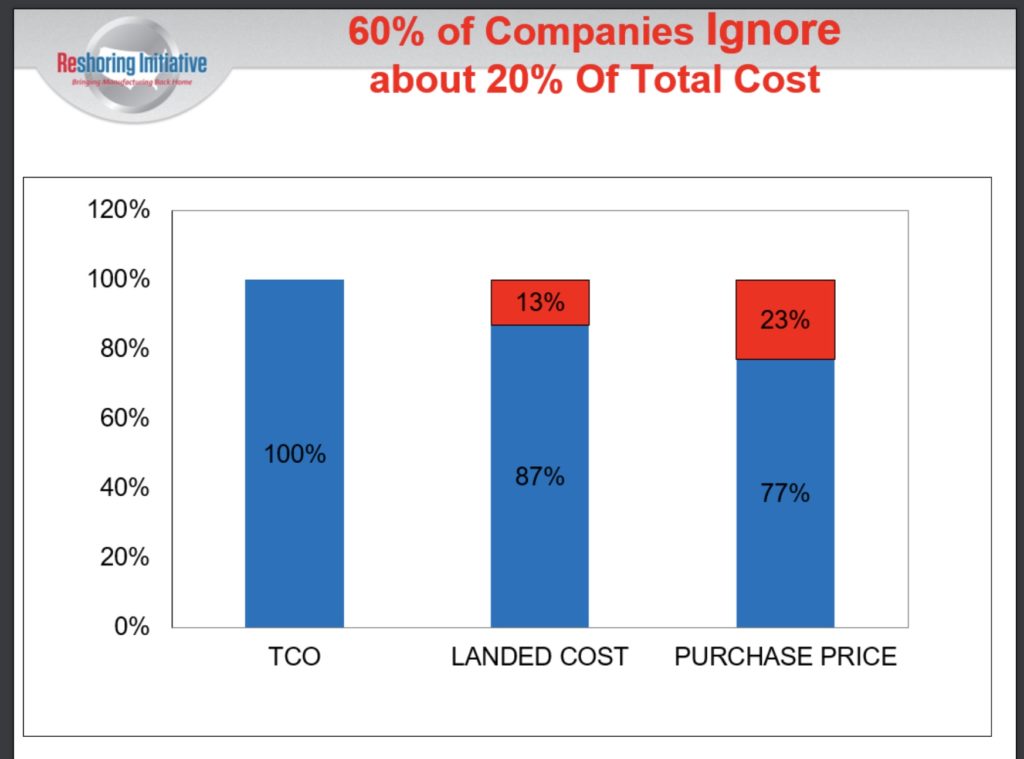

“In those situations where it makes sense economically to come back to the U.S., those companies will come back,” he explained, adding that 60% of companies currently manufacturing outside the U.S. are not accurately calculating their costs (see chart). “But those who are contemplating a return have to do the math. If they just look at wage rate vs. pricing, then very little—say, 8%—will come back. But if they look at the total cost of ownership, then 32% will likely come back. Furthermore, if they look at total cost of ownership on top of 25% Trump tariffs, then 46% will come back to the U.S. It also depends on if a particular company has the technology to be competitive.”

In either scenario, a return to U.S. production won’t likely be swift. “It took 40 years to get to the position we’re in, and it’s going to take decades to figure our way out,” Moser said. “It’s not going to happen overnight.”